I watched 102 films in 2014. Some viewings were repeats, most were first time, almost all were from prior years. Living on the college time + money budget, getting to the theater was difficult, so I relied heavily on Netflix and old DVDs. Here’s the full list of everything I watched, with some comments when warranted.

True Swill

Seven Chances (1925) by Buster Keaton – 20/100

Racist smut.

Awful

Three Ages (1923) by Buster Keaton – 30/100

Triple Trouble (1918) by Charlie Chaplin – 40/100

The Knockout (1914) by Charles Avery – 45/100

Bad

Go West (1925) by Buster Keaton – 50/100

Orphans of the Storm (1921) by Buster Keaton – 50/100

The Birth of a Nation (1915) by D.W. Griffith – 50/100

100 for the production, 0 for the overt racism and historical inaccuracy. Averaged out to 50.

Between Showers (1914) by Henry Lehrman – 55/100

Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928) by Buster Keaton – 60/100

Broken Blossoms (1919) by Buster Keaton – 60/100

Intolerance (1916) by D.W. Griffith – 60/100

Probematic

The Pawnshop (1916) by Charlie Chaplin – 65/100

Our Hospitality (1923) by Buster Keaton – 66/100

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) by Steven Spielberg – 69/100

Indian people eating monkey brains and eyeball soup? Oh man, is this movie racist.

Seven (1995) by David Fincher – 70/100

The Lady Vanishes (1938) by Alfred Hitchcock – 70/100

Abraham Lincoln (1930) by D.W. Griffith – 70/100

Sherlock, Jr. (1924) by Buster Keaton – 70/100

Easy Street (1917) by Charlie Chaplin – 70/100

The Artist (2011) by Michel Hazanavicius – 71/100

Flawed

Foxcatcher (2014) by Bennett Miller – 72/100

The Fisher King (1991) by Terry Gilliam – 72/100

Behind the Screen (1916) by Charlie Chaplin – 72/100

Dazed and Confused (1994) by Richard Linklater – 74/100

Days of Heaven (1978) by Terrence Malick – 74/100

Gravity (2013) by Alfonso Cuarón – 75/100

Way Down East (1920) by Buster Keaton – 75/100

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) by Frank Capra – 77/100

Frozen (2013) by Chris Buck & Jennifer Lee – 78/100

Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story (2004) by Rawson Marshall Thurber – 78/100 [rewatch]

American Beauty (1999) by Sam Mendes – 78/100

Casino Royale (2006) by Martin Campbell – 79/100

Good

Midnight in Paris (2011) by Woody Allen – 80/100

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998) by Terry Gilliam – 80/100

The Usual Suspects (1995) by Bryan Singer – 80/100

Badlands (1973) by Terrence Malick – 80/100

Rashomon (1950) by Akira Kurosawa – 80/100

The General (1926) by Buster Keaton – 80/100

Shanghaied (1915) by Charlie Chaplin – 80/100

Burn After Reading (2008) by Joel & Ethan Coen – 81/100

The Darjeeling Limited (2007) by Wes Anderson – 82/100

Good Will Hunting (1997) by Gus Van Sant – 82/100

Sleeper (1973) by Woody Allen – 83/100

Rope (1948) by Alfred Hitchcock – 83/100

Clerks (1994) by Kevin Smith – 84/100 [rewatch]

Raising Arizona (1987) by Joel & Ethan Coen – 84/100

Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) by Steven Spielberg – 84/100

Get Low (2010) by Aaron Schneider – 85/100

The Social Network (2010) by David Fincher – 85/100

Glengarry Glen Ross (1992) by James Foley – 85/100

Die Nibelungen: Kriemhild’s Revenge (1924) by Fritz Lang – 85/100

Classics

Nightcrawler (2014) by Dan Gilroy – 86/100

Ghostbusters (1984) by Ivan Reitman – 86/100

What’s Up, Tiger Lilly? (1966) by Woody Allen – 86/100

A Fistful of Dollars (1964) by Sergio Leone – 86/100

One A.M. (1916) by Charlie Chaplin – 86/100

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) by Wes Anderson – 87/100

The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou (2003) by Wes Anderson – 87/100 [rewatch]

Caddyshack (1980) by Harold Ramis – 87/100 [rewatch]

From Russia With Love (1963) by Terence Young – 87/100

Rushmore (1998) by Wes Anderson – 88/100 [rewatch]

Saving Private Ryan (1998) by Steven Spielberg – 88/100

Broadway Danny Rose (1984) by Woody Allen – 88/100

Raging Bull (1980) by Martin Scorsese – 88/100

Dr. No (1962) by Terence Young – 88/100

The Apartment (1960) by Billy Wilder – 88/100

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) by John Huston – 88/100

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) by Martin Scorsese – 89/100 [rewatch]

Bernie (2012) by Richard Linklater – 89/100

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) by Steven Spielberg – 89/100

Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask) (1972) by Woody Allen – 89/100

Marvels

The Maltese Falcon (1941) by John Huston – 90/100

Battleship Potemkin (1925) by Sergei Eisenstein – 90/100

Strike (1925) by Sergei Eisenstein – 90/100

12 Monkeys (1995) by Terry Gilliam – 91/100

Blazing Saddles (1974) by Mel Brooks – 91/100 [rewatch]

Die Nibelungen: Siegfried (1924) by Fritz Lang – 91/100

Silver Linings Playbook (2012) by David O. Russell – 92/100 [rewatch]

Love and Death (1975) by Woody Allen – 92/100

The Last Detail (1973) by Hal Ashby – 92/100 [twice]

Sunset Blvd (1950) by Billy Wilder – 92/100

The Immigrant (1917) by Charlie Chaplin – 92/100

Nebraska (2013) by Alexander Payne – 93/100

Barton Fink (1991) by Joel & Ethan Coen – 93/100

Young Frankenstein (1974) by Mel Brooks – 93/100 [rewatch]

True Genius

Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) by Wes Anderson – 94/100

Lost in Translation (2003) by Sofia Coppola – 94/100

Boogie Nights (1995) by Paul Thomas Anderson – 95/100

Nosferatu (1922) by F.W. Murnau – 95/100

Boyhood (2014) by Richard Linkater – 96/100

The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) by Wes Anderson – 96/100 [rewatch]

Citizen Kane (1941) by Orson Welles – 96/100 [rewatch]

Metropolis (1927) by Fritz Lang – 96/100

Fargo (1996) by Joel & Ethan Coen – 97/100 [twice]

Taxi Driver (1976) by Martin Scorsese – 97/100

Paths of Glory (1957) by Stanley Kubrick – 97/100

The Godfather (1972) by Francis Ford Coppola – 98/100

The Cranes Are Flying (1957) by Mikhail Kalatozov – 99/100

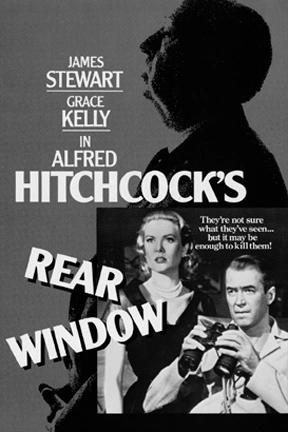

Rear Window (1954) by Alfred Hitchcock – 99/100 [twice]

There Will Be Blood (2007) by Paul Thomas Anderson – 100/100

Apocalypse Now (1979) by Francis Ford Coppola – 100/100

Psycho (1960) by Alfred Hitchcock – 100/100

A full list of all of my film ratings can be found here:

http://www.criticker.com/profile/djcrawfo/

Here’s to a great 2015 of movie watching!